When Architect Left

Year:

Studio:

Site:

Type:

Collaboration:

Tutor:

Studio:

Site:

Type:

Collaboration:

Tutor:

Msc3 / 2020

Heritage

Bijlmer, NL

Research

Individual

Nicholas Clarke

Heritage

Bijlmer, NL

Research

Individual

Nicholas Clarke

Architecture without ‘architects’ as a ramification of modern urbanism

In the industrialization of building, the overpower of technology symbolized the domination of abstract, instrumental reason over humans and nature with orderly purified forms. Housings built in the modern age were designed to glorify this ‘machine style’ while simultaneously alleviating some of the worst living circumstances. In the early twentieth century, this sudden unexpected intervention of a new ability that abruptly seemingly solved a previously unsolvable problem - the social, economic, technical and artistic questions. However, the solution had come at a price. In the integration of people into rationalised mass production, this instrumental reason fetishized the technological means to human ends, which were conceived as developing according to a determinate logic beyond human contro. In fully banking on the power of industry over the skills of the craftsman, its over dominance had made the architect as craftsman redundant. Since then, the modern architect had left the stage leaving mass propagation of ‘living machines’ determined by plutocracy and technocracy.

During the modern movement, architecture was nothing to be inherited but acquired. Housing in the era of machinery was studied what was there, what was invented, and then was processed by typological variations. Form had been following form, following the unexpected upcoming failure. The emergence of liveability problems in the residential neighborhood area designed under the name of modern urbanism had deviated from the egalitarian utopian manifestation. In the late 70s and 80s, most of the bourgeois had given up hope on those massive concrete jungles and left, leaving the rest of the working class engulfed by those forms. The abandonment of style and taste had removed a bourgeois instrument to perpetuate class distinctions, but it did not kill the social class. Instead, the succession of anonymous buildings and the stripped of the presence of the author had embedded the inhabitants, in which most of them were working class, along, being anonymous and neglected.

Be a ‘non-architect’ in the justification of neighbourhood

Following the crisis of modern urbanism was not the grand return of the architect. Instead, a series of demolitions of those neighborhoods was taken in the hope of eradicating the liveability problem as well. The failure of the manifesto in creating a clean, classless society had provoked the residents’ desire back for the traditional housing. Counter movements and actions, followed by more reactions, were then carried out to remediate the residential urban structure. The backlash of urban modernism was merely a social reaction, with no more heroic manifestation. The Bijlmermeer neighbourhood, one of those modernist urban projects, has also witnessed and experienced a series of tragedies and remediations as a victim of the failure of the experiment. For those massive slab housings created in the 1960s, on behalf of the CIAM manifestation, many of them have been replaced by parks and playgrounds, and lowrise midrise buildings in the late 20the century. The ‘Anti-Bijlmer’ movement in the 70s/ 80s attempted to normalise the neighbourhood by looking backwards to the traditional housing, was just another ramification of the remediation of those unwanted housing stock. And what the normalization of the grand modernism failure left us today is a ‘generic junk’ of even more anonymous, ‘non-styled’ 70s/ 80s housing.

In the era of modernism, the value of every invention lies in what it maquettes unnecessary, in the elimination of redundant processes. When the regime of design discussion among architects did not even exist amidst the erection of the mass housing production, apparently, the architects were not expected to play a hero in the partial or total demolition of them in the late 20th century, nor the design of those ‘anti-Bijlmer’ residential buildings. Followed by the decline of the architectural heroism, there is no ‘style’ in the residential buildings from the 70s/ 80s in Bijlmer.

Bijlmer neighborhood, as an experimental product with no grand vision of architecture, nor architectural style, I am intrigued by the possible ways to justify or deny the existence of its mass ramifications through a non-traditional architectural lens. It is indisputable that they consisted of tangible attributes as they were constructed as a physical entity. They are architecture, a communication agency from the past. However, embedded under those attributes, they might be something more, with parentheses for its corresponding values or none. Undergone a dynamic continuity for almost half a century, these buildings and areas are not old enough to be regarded as heritage, but old enough for the next phase of change or anti-change. To interrogate the possible destiny of these residential neighbourhoods, assessment of the underlying values and problems is urged. And to prepare the next chapter for the ‘new heritage’, we do not only need architectural professionals, but more importantly, passing the validation to those ‘non-architect’ to determine the value of those architecture without ‘architects’.

Spatiality of injustice in the lack of diversity of the commons

While social justice could be understood as the distribution of goods, such as utility and liberty, ‘spatiality of injustice’ refers to the physical attributes and social space that sustain the production of injustice. To further consolidate this idea, in a context of a neighborhood, it would be interpreted as ‘the neighbourhood commons which causes uneven distribution of the common goods - the economic, social and cultural capital’.

Rooted in the neoliberal critique of contemporary urban development in commodifying the collective resources of the city, there is a powerful social movement to reclaim control and promote greater access of urban space and resources. Henri Lefebvre, a French philosopher, first articulated the ‘right to the city’ movement which has manifested to give more power to city inhabitants in shaping urban space. Although the definition of the ‘right’ to the urban space by the scope of enhanced participation and access to urban resources remains politically unclear, where this research lays the interest in is the ‘collective shaping of the urban space’ which facilitates the distribution of common goods. Thus, regarding a neighbourhood scale, instead of ‘urban commons’, ‘neighbourhood commons’ is the key spatial constituent in the distribution of common goods as an inclusive and obvious confluence of most collective activities. Following the framework of ‘neighbourhood commons’ and ‘injustice’ is the clarification of the causal relation in between. Although the issue of justice has been raised in the field of geography, the factors of scale, theme and perspective have made the measurement of this political philosophy in the form of spatial principles particularly challenging. Overtime, among different streams of thoughts about the notion of spatial justice, a just form of social-spatial relationship is best represented by Suan Fainstein’s book, The Just City, suggesting three indicators: democracy, equity and diversity. Referencing these indicators in the context of the Bijlmerplein, the lack of diversity of the commons as a by-product of homogeneity masses, could be read as an underlying cause of social injustice.

The definition of the ‘commons’ could be spatially ambiguous with a spectrum of inclusiveness.

Unlike ‘public space’ which is politically well-defined by the negative violation of order,

‘commons’ is vice versa which reclaims control for groups of heterogeneous users,

often with minimal regulatory involvement. To avoid the possible misunderstanding

of the form of ‘commons’, in this research, the ‘neighborhood commons’ refers to any spaces

which intend to open up access of the resource in order to produce other common goods

or to enhance social utility for a broader class of neighbourhood inhabitants.

Unlike ‘public space’ which is politically well-defined by the negative violation of order,

‘commons’ is vice versa which reclaims control for groups of heterogeneous users,

often with minimal regulatory involvement. To avoid the possible misunderstanding

of the form of ‘commons’, in this research, the ‘neighborhood commons’ refers to any spaces

which intend to open up access of the resource in order to produce other common goods

or to enhance social utility for a broader class of neighbourhood inhabitants.

In Bijlmerplein, hindrance for an even distribution of all forms of capital can be identified as six commons categories.

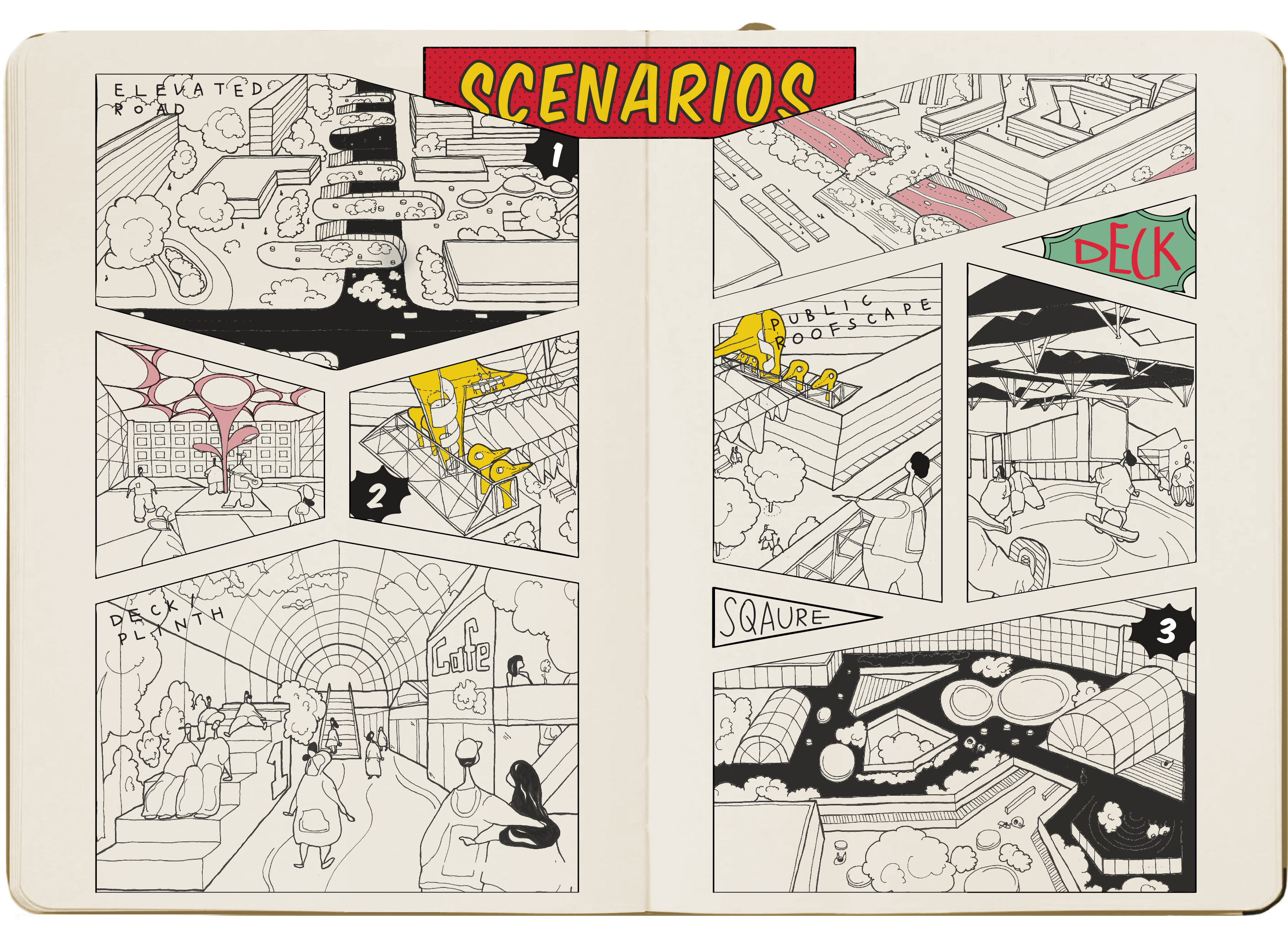

1. ELEVATED ROAD

2. PUBLIC ROOFSCAPE

3. DECK AND PLINTH

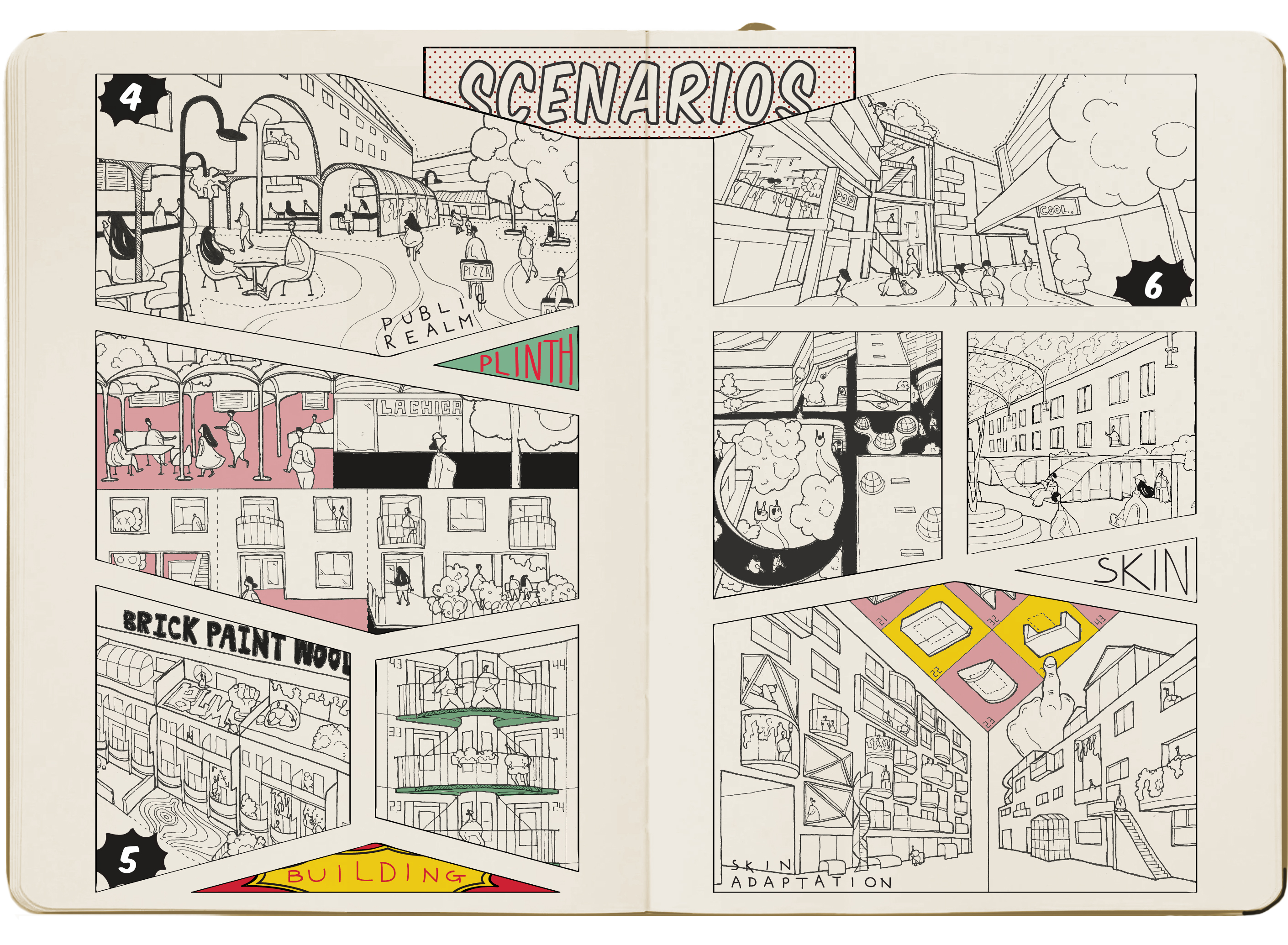

4. G/F PUBLIC REALM

5. BUILDING SKIN

6. BUILDING ACCESSIBILITY

Amplification of socio-spatial injustice amidst COVID-19

Major global events, such as economic depressions and wars have been shaping our society and the way we experience everyday life throughout history. The war gave the modernist a blank page to experiment with the ‘clean and neat’ utopian city, followed by the global failure of those mass produced slab housing urging the demolition of them. Pandemics in 2020 is one of them which demands a major shift in functional physical approaches of places as well. As pandemic regulations are being implemented throughout the globe, there is a behaviour shift in the public and human interactions. Socially, environmentally, and also economically, open spaces play an essential role in maintaining a balanced public health amidst Covid-19. Witnessing the adaptation of city and citizens in this crisis, open urban commons has been proven its key to build on the sense of community and social cohesion while overcoming the economic challenges. While high quality of existing commons acts as a catalyst for the transition of the ‘new normal’, problematic ones, or the lack of neighbourhood commons becomes an amplifying device of social injustice in a neighbourhood.

The crisis of pandemic does not only raise a challenge in social activities, but also more significant in the form of economic capital. As an experimental neighborhood serving as a product of Anti-Bijlmer, the idea of separation of function, Bijlmerplein had intention to be a mix-use area with shopping streets, shopping plinth and arcade on the ground level with housing above. Throughout decades since its integration of consumptional leisure, Bijlmerplein has proved its higher level of resilience compared to other monofunctional neighbourhoods. Shops had been bringing more active street life and public realm to Bijlmerplein and hence, attracting higher influx of inhabitants compared to other neighbourhoods in the H-buurt. However, the paradigm shift in consumer behaviour to online in recent decades, with the noticeably escalating trajectory of online consumption amidst the pandemic, a lot of stores have been found vacant today in Bijlmerplein. The decline of the number of people spending time outdoors is limited by the lack of choices of outdoor space, as a consequence of less potential customers on the streets, causing closing down of more stores. On the other hand, under a circular effect, the shrinking spectrum of surviving shops on the ground floors has constituted a ‘deadly’ vibes of the public realm, which further suppresses the residents from getting on the street. The diminishing public realm has raised an alarm on the impact of pandemic and potential economic crisis on the social resilience of Bijlmerplein under the paradigm shift in consumer behavior.

So...

How is social injustice deepened in the lack of diversity of neighborhood commons amidst the crisis of pandemic?

How can we strategize the enhancement of neighbourhood commons, based on the value of the existing attributes, towards a more just neighbourhood for the post-covid future?